Vasculitis Diagnostics

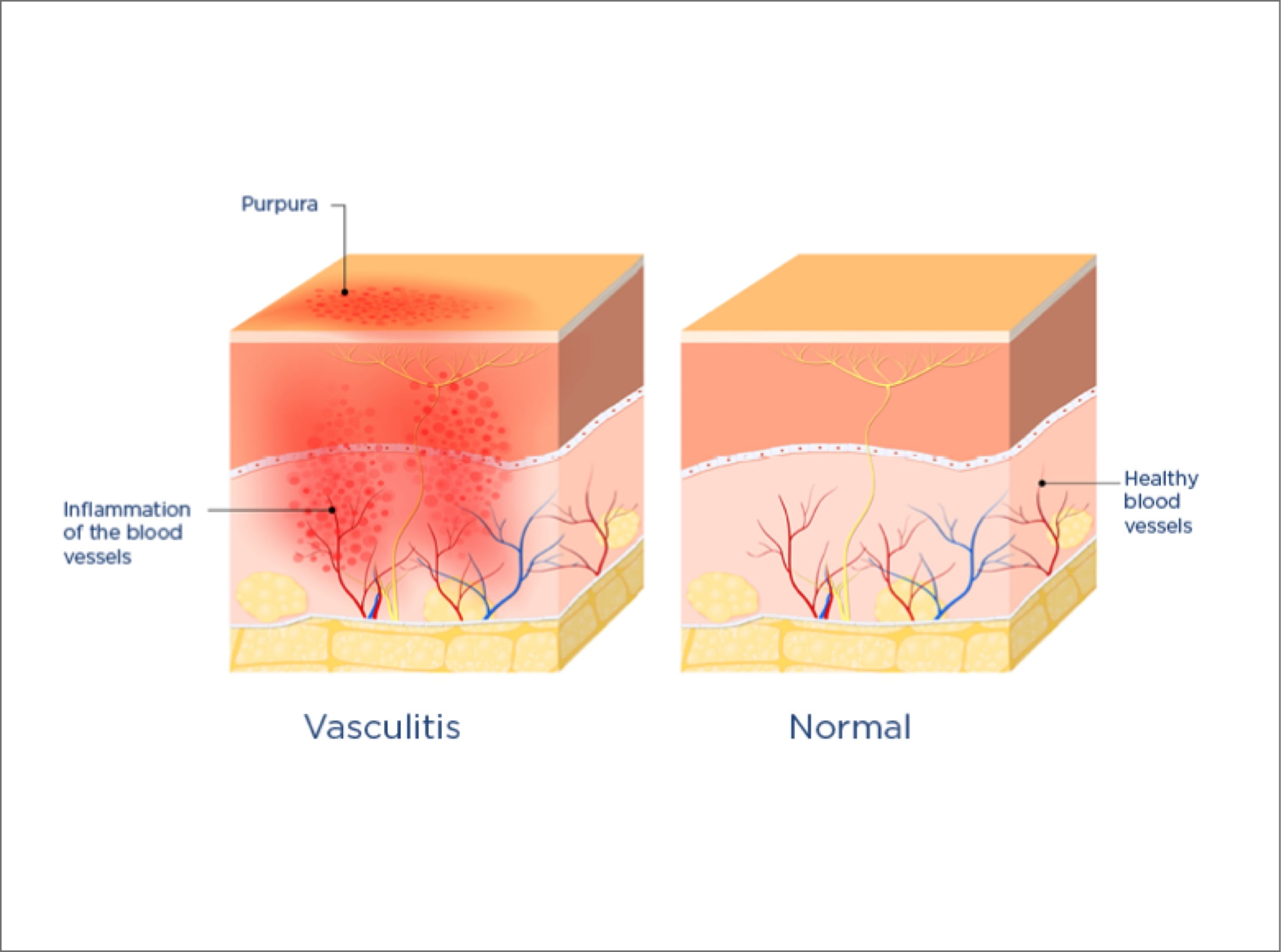

Vasculitis—also known as angiitis or arteritis—is defined as inflammation of the blood vessels. Many conditions comprise vasculitis and are collectively referred to as vasculitides. A number of tests can be used to diagnose vasculitis types, and treatment usually involves two phases: controlling the inflammation to achieve remission, and maintenance treatment to prevent relapse. This post will explore what vasculitis is, how vasculitides can be classified and key types of treatments.

Vasculitis Types and Treatments

Typically, vasculitides are rare. They are characterized by inflammation at several blood-vessel sites and death of blood-vessel cells. They may affect one organ or many organs. Importantly, vasculitides may range from minor, local, self-limiting disease to severe, widespread disease. Vasculitis may be either acute (short-term) or chronic (long-term).

There are many different types of vasculitis, and their occurrence varies according to patient age, sex, and geographic location.1 Specific types of vasculitis appear to affect particular populations. In Northern Europe, for instance, a type called granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is most common. In Southern Europe, a related type—microscopic polyangiitis (MPA)—is most common. The reasons for such differences are unclear. However, inherited factors and the presence of environmental toxins might provide some explanation.²

The anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides (AAV) are a diverse group of rare diseases. Key features include inflammation and cell death in small and medium blood vessels, and the presence of ANCAs. The three main AAVs are:³ ⁶

- Microscopic polyangiitis (MPA)

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA; or Wegener's granulomatosis)

- Eosinophilic GPA (EGPA; or Churg-Strauss syndrome)

Epidemiology of Vasculitis

Overall, the incidence (number of new cases per year) of vasculitis has been reported as approximately 20–54 cases per 1 million population, but this varies widely.³⁻⁴

A recent UK study reported the incidence of temporal arteritis as 130–300 per million in individuals aged over 50 years. The incidence of Kawasaki disease was reported as 55–84 per million in children aged under 5 years.⁵

The overall annual incidence of AAV has been reported with wide-ranging values of approximately 10–33 per million.³ ⁷⁻⁸ Considerable geographic variation exists in the occurrence of AAV. Nonetheless, in Asia, the most common AAV appears to be MPA that is positive for myeloperoxidase enzyme (MPO). In Northern Europe and the USA, the most common AAV appears to be GPA that is positive for leukocyte proteinase 3 (PR3).9 In AAV, MPO and PR3 are proteins inside white blood cells (neutrophils) that are targeted by ANCA antibodies. This is part of the disruption that can occur to autoimmune systems, as mentioned earlier.

Etiology and Pathophysiology of Vasculitis

The precise causes of vasculitis is not yet fully understood. However, some types of the disease may be inherited. Others may be due to autoimmune disorders (i.e., when the immune system attacks blood-vessel cells by accident). Likely triggers of such immune system disruption are:

- Drug side effects

- Hematologic (blood) cancers

- Specific autoimmune diseases — e.g., lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and scleroderma (skin contraction and hardening)

- Surgery

- Ultraviolet light

- Viral infections — e.g., hepatitis B or C

When affected by vasculitis, blood vessels become inflamed and may bleed. Inflammation leads to thickening of blood-vessel walls, which, in turn, leads to blockade of the actual blood-vessel tubes. This means that the amount of blood, oxygen, and essential nutrients reaching tissues and organs is reduced.

Vasculitis can affect anyone regardless of age, sex, or race. However, the likelihood of developing the disease increases with:

- Smoking cigarettes

- Long-term infections, such as hepatitis B or C

- Autoimmune conditions such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, or scleroderma

Additional problems arise from severe vasculitis, or from side effects of prescription drugs used to treat vasculitis. These problems may include:

- Aneurysms (bulging of blood-vessel walls) or blood clots, which may lead to heart attack or stroke

- Blindness or vision loss, especially with an untreated type of vasculitis called giant cell (temporal) arteritis

- Infections, such as meningitis, pneumonia, and sepsis (blood poisoning)

- Major organ damage

Classifying Types of Vasculitis

The Chapel Hill Consensus Conference (CHCC) classification of vasculitides was updated in 2012. This classification system is primarily a naming system. It is not designed for clinical research or diagnosis and steering of treatment decisions.⁹⁻¹⁰

Large-vessel vasculitis, which affects the

aorta and its main branches, but also arteries

of any size:

-

• Giant cell (temporal) arteritis

• Takayasu arteritis

Medium-vessel vasculitis, which affects the

key arteries to organs and their branches:

-

• Kawasaki disease

• Polyarteritis nodosa

Small-vessel vasculitis:

-

• ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV):

• Immune complex small-vessel vasculitis, with some or considerable build-up of

immunoglobulin in blood-vessel walls:• Microscopic polyangiitis (MPA)

• Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA)

• Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (EGPA)• Anti-glomerular basement membrane disease (Goodpasture's syndrome)

• Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis

• Immunoglobulin A vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein purpura)

• Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis

Variable-vessel vasculitis, with no principal

size defined for the vessels affected:

-

• Behçet's disease

• Cogan's syndrome

Single-organ vasculitis:

-

• Cutaneous leukocytoclastic angiitis

• Cutaneous arteritis

• Primary central nervous system vasculitis

• Isolated aortitis

• Others

Vasculitis associated with systemic disease:

-

• Lupus vasculitis

• Rheumatoid vasculitis

• Sarcoid vasculitis

• Others

Vasculitis associated with probable etiology:

-

• Hepatitis C virus-associated cryoglobulinemic vasculitis

• Hepatitis B virus-associated vasculitis

• Syphilis-associated aortitis

• Drug-associated immune complex vasculitis

• Drug-associated ANCA-associated vasculitis

• Cancer-associated vasculitis

• Others

| The CHCC system defines [9, 10]: | |

|---|---|

|

Large-vessel vasculitis, which affects the |

• Giant cell (temporal) arteritis |

|

Medium-vessel vasculitis, which affects the |

• Kawasaki disease |

|

Small-vessel vasculitis: |

• ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV): • Immune complex small-vessel vasculitis, with some or considerable build-up of • Microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) • Anti-glomerular basement membrane disease (Goodpasture's syndrome) |

|

Variable-vessel vasculitis, with no principal |

• Behçet's disease |

|

Single-organ vasculitis: |

• Cutaneous leukocytoclastic angiitis |

|

Vasculitis associated with systemic disease: |

• Lupus vasculitis |

|

Vasculitis associated with probable etiology: |

• Hepatitis C virus-associated cryoglobulinemic vasculitis |

Why Diagnosing Vasculitides is Important

Diagnosing vasculitides is difficult, partly because the disorders are so rare. The numerous signs and symptoms of the conditions are typically linked to reduced blood flow and may affect any organ. The signs and symptoms may also be easily confused with other, more common diseases (e.g., influenza, upper respiratory infection, stroke, and inflammatory bowel disease). Therefore, a diagnosis of vasculitis may often be missed or delayed. Numerous tests and assessments are often needed before a definite diagnosis of vasculitis can be made.

Nonetheless, it is particularly important to diagnose vasculitides as early as possible. Suitable treatment can then be started. Appropriate treatment will differ depending on whether vasculitis is the primary condition or secondary to infections or other drug treatment. Any delay in starting treatment may lead to permanent tissue or organ damage, and some types of vasculitis are life-threatening.¹¹

The tests and assessments used to diagnose vasculitides vary according to the specific type of vasculitis involved. However, the doctor will initially take a medical history and conduct a physical exam. Then, any or all of the following tests and assessments may be needed to confirm or deny the presence of vasculitis:

- Blood tests: Protein levels (e.g., C-reactive protein) in the blood can indicate inflammation. A complete blood count can also indicate anemia (a shortage of red blood cells [RBCs; erythrocytes]) or other important information. Generally, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) >100 mm/hour indicates vasculitis, heart infection (infective endocarditis), or cancer.

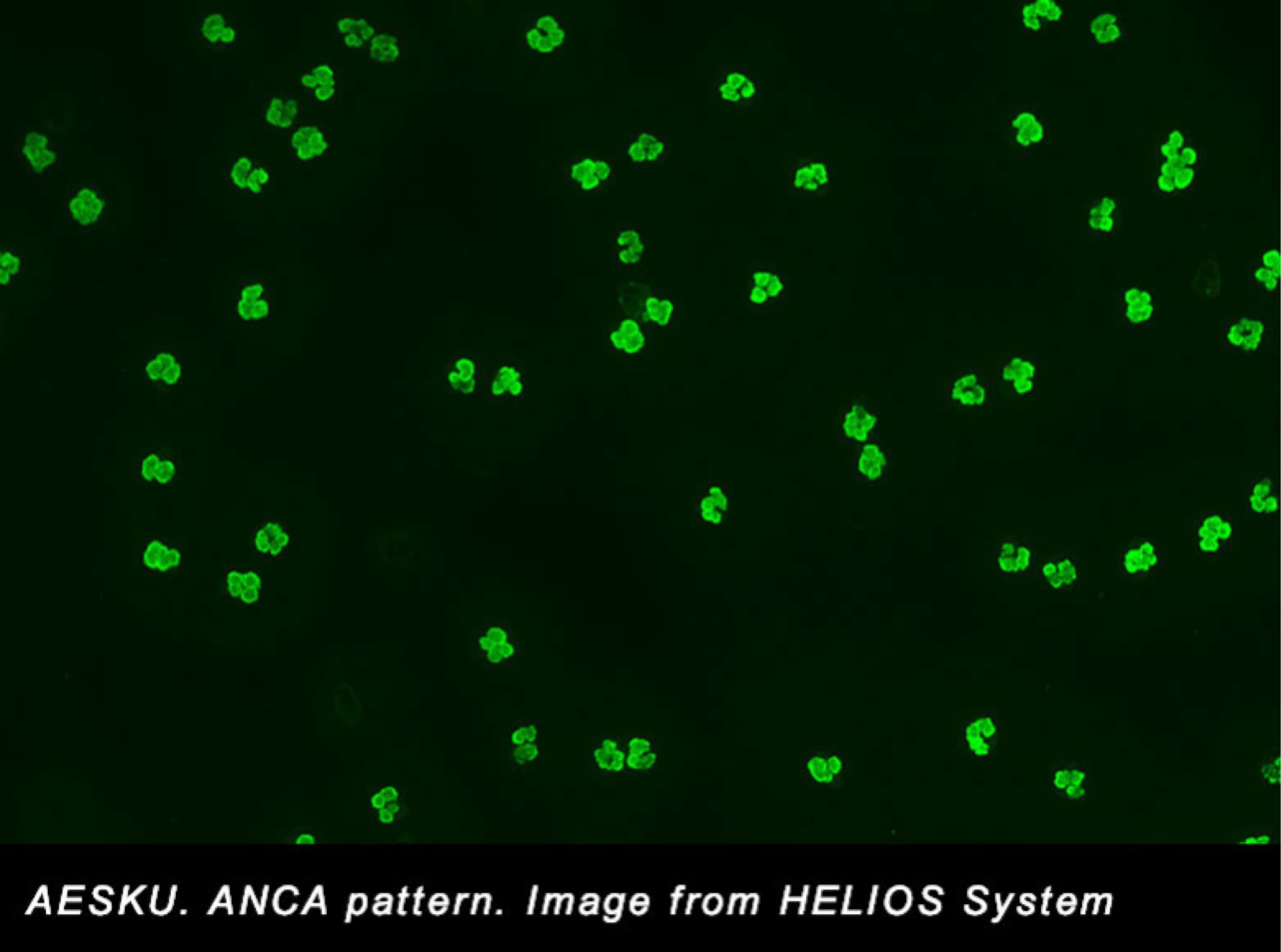

- Immunology tests: ANCA autoantibodies are a particularly useful indicator of ANCA-associated vasculitides (AAV) — MPA, GPA, and EGPA. ANCA antibodies are identified in the serum of patients with an indirect immunofluorescence assay There are two principal types of ANCA:

- Cytoplasmic or c-ANCA, which attach to PR3 inside neutrophils

- Perinuclear or p-ANCA, which attach to MPO inside neutrophils

Up to 80% or more of patients with GPA will have the presence of c-ANCA–PR3. In patients with MPA, the presence of p-ANCA–MPO is more common.6, 11 The differences between disease associated with c-ANCA and that linked with p-ANCA have important implications for treatment.

- Urine tests: These can indicate whether urine contains RBCs or excess protein, which might be problematic.

- Imaging tests: Tests from outside the body—such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), ultrasound, and x-rays—are used to identify the blood vessels and organs affected by vasculitis. These tests also help doctors determine whether or not a patient has responded to treatment.

- Angiographic assessments: These assessments take x-rays of blood vessels. A bendable, thin tube (catheter) is introduced into a large artery or vein. An injection of a contrast medium (or dye) is then made via the catheter. X-rays are taken, and the structure of blood vessels is viewable.

- Biopsy: During this surgery, a small tissue sample is taken from affected areas of the body. The sample is then analyzed microscopically for any indication of vasculitis.

Treatment of Vasculitis

Treatment is based on numerous factors including the specific type of vasculitis, symptoms, disease severity, organs affected, age, lab results, overall health, and more. Treatment usually involves two phases: controlling the inflammation to achieve remission, and maintenance treatment to prevent relapse.

Treatments for vasculitis include the following:

- Corticosteroids are often the first line of treatment to reduce inflammation (i.e., prednisone)

- For more serious forms of vasculitis, medications that suppress the immune system (immunosuppressors) are prescribed, including methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide and mycophenolate mofetil

- Biologic agents such as rituximab, tocilizumab, and mepolizumab may be prescribed for specific types of vasculitis

For very severe cases, other additional treatments include plasmapheresis (plasma exchange), intravenous gamma globulin, or surgery to restore blood flow.

Scientific materials

References

- Watts RA, Lane SE, Scott DG, Koldingsnes W, Nossent H, Gonzalez-Gay MA, Garcia-Porrua C, Bentham GA. Epidemiology of vasculitis in Europe. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001; 60:1156–7. PUBMED link

- Lane SE, Scott DG, Heaton A, Watts RA. Primary renal vasculitis in Norfolk--increasing incidence or increasing recognition? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000; 15:23–7. PUBMED link

- Reinhold-Keller E, Herlyn K, Wagner-Bastmeyer R, Gross WL. Stable incidence of primary systemic vasculitides over five years: results from the German vasculitis register. Arthritis Rheum. 2005; 53:93–9. PUBMED link

- Scott DG, Watts RA. Systemic vasculitis: epidemiology, classification and environmental factors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000; 59:161–3. PUBMED link

- Watts RA, Mooney J, Scott DG. The epidemiology of vasculitis in the UK. Rheumatology. 2014; 53: i187. link

- Cornec D, Cornec-Le Gall E, Fervenza FC, Specks U. ANCA-associated vasculitis - clinical utility of using ANCA specificity to classify patients. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016; 12:570–9. PUBMED link

- Berti A, Cornec D, Crowson CS, Specks, M.D., U and Matteson, M.D., M.P.H., EL.The epidemiology of ANCA associated vasculitis in the U.S.: A 20 year population based study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017; 69(12): 2338–2350. PUBMED link

- Pearce FA, Lanyon PC, Grainge MJ, Shaunak R, Mahr A, Hubbard RB, Watts RA. Incidence of ANCA-associated vasculitis in a UK mixed ethnicity population. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016; 55:1656–53. PUBMED link

- Katsuyama T, Sada KE, Makino H. Current concept and epidemiology of systemic vasculitides. Allergol Int. 2014; 63:505–13. PUBMED link

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, Basu N, Cid MC, Ferrario F, Flores-Suarez LF, Gross WL, Guillevin L, Hagen EC, Hoffman GS, Jayne DR, Kallenberg CG, Lamprecht P, Langford CA, Luqmani RA, Mahr AD, Matteson EL, Merkel PA, Ozen S, Pusey CD, Rasmussen N, Rees AJ, Scott DG, Specks U, Stone JH, Takahashi K, Watts RA. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013; 65:1–11. PUBMED link

- Suresh E. Diagnostic approach to patients with suspected vasculitis. Postgrad Med. 2006; 82:483–8. PUBMED link